The Life of Salvationist

Henry F. Milans (1861-1946) Reaches into the 21st Century

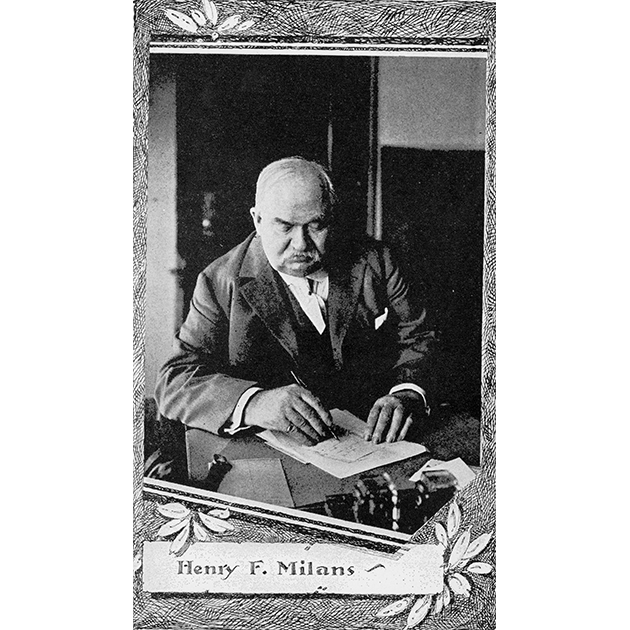

I learn the depths to which I have sunk, from the length of the chain let down to updraw me. I ascertain the mightiness of the ruin, by examining the machinery for restoration.” Henry F. Milans would relate that thought to thousands after escaping the degradation of alcoholism by finding his way to The Salvation Army. His life is a reminder of the tapestry of redemption one individual can weave into a pattern that stretches across generations, families and cultures.

Young Henry and family had moved from Pennsylvania to Washington DC by the end of the Civil War, where his father, a prominent lawyer, had accepted the job of County Jailor as a political award. By his early 20s, Henry was already a prominent newspaper editor, known for the innovative use of photos and layout as managing editor of the New York Daily Mercury. He had a lovely wife and a fine home. However, he had a penchant for drink. By age 30, his alcoholism was in full force, costing him one position after another and his marriage. Blacklisted, penniless and out of work, he found himself in New York City’s Bowery, trading all his possessions, right down to his shoes, for “whiskey credit.”

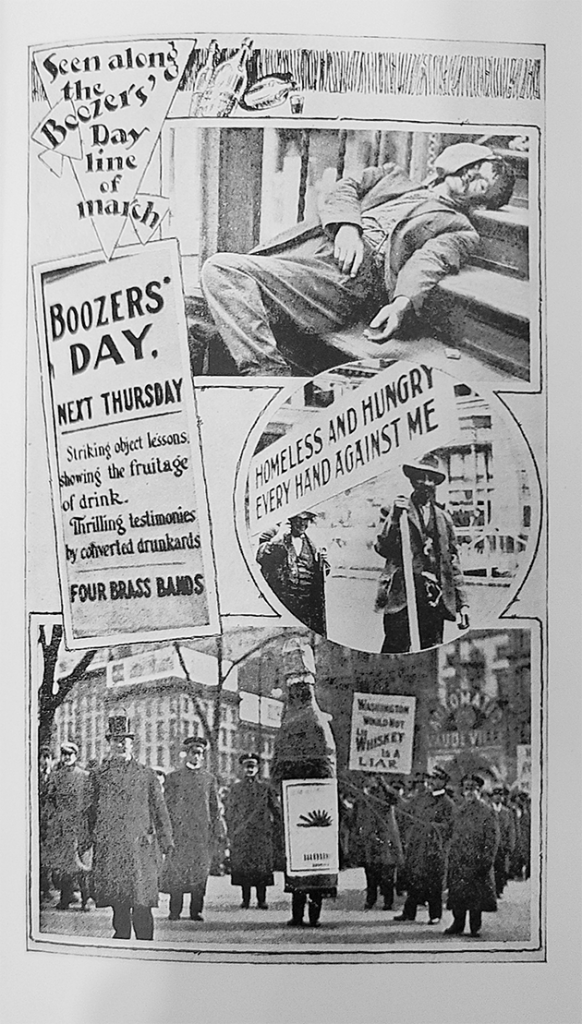

By 1908, he was diagnosed as hopelessly incurable by the doctors at Bellevue Hospital in New York. Back on the streets, he heard about a “Boozer’s Convention,” which, in his words, “consisted of a whole regiment of ‘Salvationists’ compelling the bums, drunkards, ne’er-do-wells and broken pieces of nondescript humanity to submit to being directed, led or carried to The Salvation Army Memorial Hall on West 14th Street for the purpose of being invited, coaxed or jarred out of their hopelessness and worthlessness into conversion and good citizenship.”

There, Henry F. Milans fell to his knees at the penitent form and poured out his soul to God in an agony of desire—not for whiskey this time, but for deliverance from its power.

Milans recalled, “It was the Master, and down into the depths of hell there groped a hand—a nail-pierced hand—which found the man it sought and lifted him out. The miracle was performed.”

Nearly 20 years later, his marriage restored, career renewed, and life in order, he recalled, “From that moment I have never been tempted to take a drink of anything with alcohol in it.” Passionate to share the hope he had found, Milans spent the rest of his life traveling and speaking at Salvation Army rallies, conventions, churches and auditoriums about the salvation and deliverance he had found in Christ. He embarked on a letter writing campaign, reaching out to alcoholics and their families all over the world.

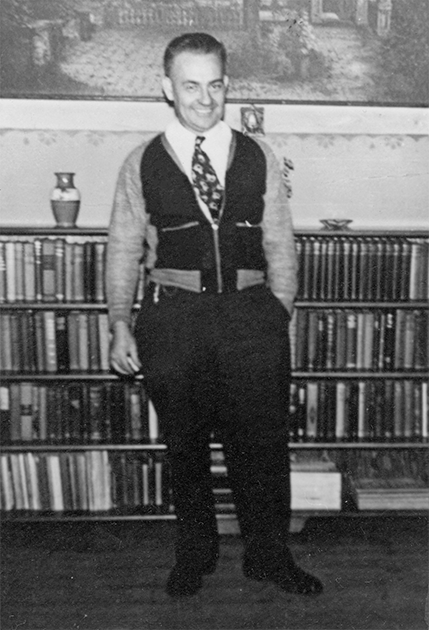

Charles Slocum was one individual Henry F. Milans was able to reach.

Charles Edward Slocum was born in a stable at a horse racetrack somewhere in New York in 1903. He was carted from track to track with his mother Orpha and father William, a jockey.

Charlie’s father, William Slocum, sailed to America in 1875, at the age of two, with his mother to escape the abject poverty in the slums of Liverpool, England. They were certain they would find a wonderful life in America. But hope died when Will’s longshoreman father died of typhoid fever shortly after their arrival. Will’s dying mother placed young Will and his brother in the Catholic orphanage at York. His growth stunted from malnutrition, Will was a “good mark” for the promoter combing orphanages looking for boys to become jockeys. Promised $18 and a new suit of clothes after a four-year apprenticeship, Will’s life at age 13 was looking up.

Young Will excelled as a jockey and by 1900, had grown into a dapper young man sporting fine clothes, a gold watch, and admiring young women. He won the eye of Orpha Reynolds. Gambling and alcohol addiction were common to the racing circuit, and no doubt Orpha was unable to endure life as the wife of a jockey. She left when Charlie was only three.

Will and young Charlie followed the racing circuit from Saratoga Springs, New York to Tijuana, Mexico, and the glamourous tracks of Florida. At one time, Will rode the famous horse, “Man of War.” No doubt Charlie got his first taste of the bottle as a teen, and by early adulthood he was hopelessly hooked, certainly an alcoholic before the age of 25.

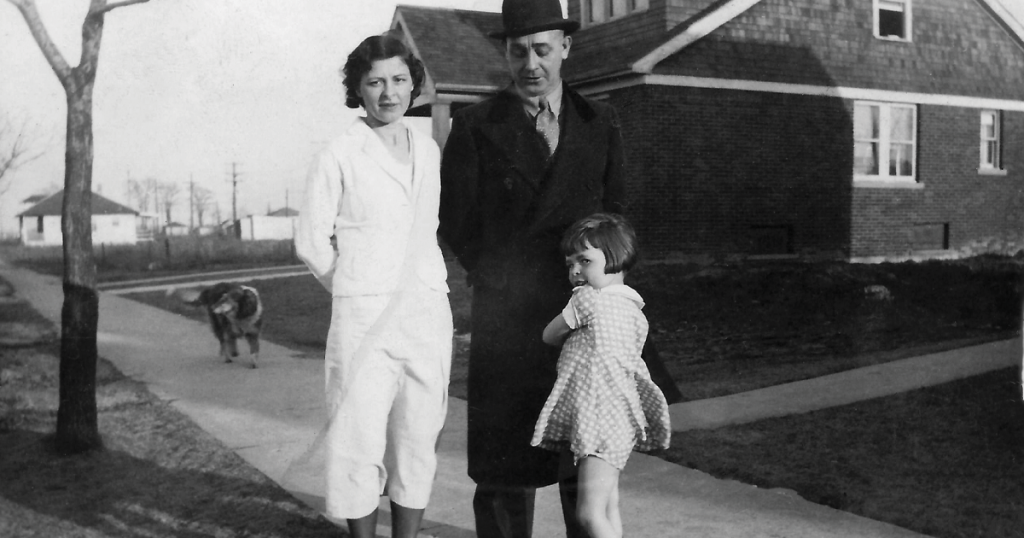

In 1930, Charlie met the widow Olive Hannah Warren Davis, and they were married in a simple ceremony in Ohio. In 1932, Charles and Olive had a daughter, Charla Joann, but by 1936, his alcoholism was destructive. On Christmas Eve in Detroit, 1936, Olive Davis sent her husband Charlie out with $5, and instructions to find the best Christmas tree he could get. A quick stop at a saloon led from one drink to several. Thrown out of the saloon, Charlie slipped and fell face down in the gutter. Horrified, Charla began crying out to passersby for help. She looked up, and there stood the shining face of a man in uniform looking like a soldier. It was 1936, years before WWII, and the only uniformed men out on Christmas Eve were The Salvation Army bell ringers. The good Samaritan helped them home and disappeared as quickly as he appeared.

Charlie’s desperate state only got worse. In 1939, with Christmas just around the corner, Olive glanced at the cover of Liberty Magazine and the words “Alcoholics and God” jumped off the page. She found the article about two men from Akron, Ohio who claimed to have found a cure for alcoholism.

She telephoned Dr. Bob Smith, who insisted she bring Charlie down to Akron without delay. That weekend she loaded up the old Buick and she and Charlie set out for Akron. There she turned Charlie over to the care of Dr. Bob and his partner Bill Wilson, the founders of a new group called Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). After a few days, she and a sober Charlie returned home to Detroit. They opened their home on Manning Avenue and started the first AA meetings in Detroit.

By early 1940, three new meetings had started throughout Detroit. Hearing of their success, in 1941, Salvationists from the Citadel in Detroit invited Charlie to come share with them about what was happening with this fast growing new movement known as AA. Leaving his work as a newspaper pressroom foreman at the Detroit Times, he struck out for the Citadel.

As he approached, he could hear the booming voice of a preacher coming from the Salvation Army mission on the street. Peering inside, he was captivated as the animated newspaperman shared stories of his life, his failures and his miraculous redemption. Henry F. Milans had been preaching at the Detroit mission for weeks. There Charlie fell to his knees at the penitent form and met his Savior. Like Henry, it was a miraculous deliverance. AA had served to get Charlie sober, but only Christ could make it eternal.

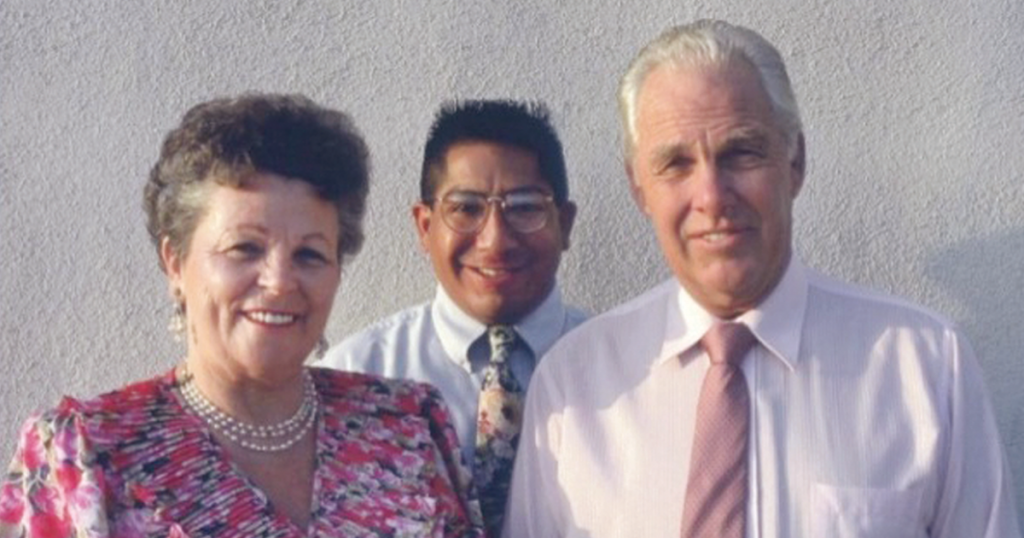

Charlie got home that night and shared his story with Olive who was overjoyed, and insisted she wanted to meet the former drunk newspaperman to extend her gratitude. What providence! Two former drunk newspapermen finding one another on the Detroit Bowery. The next night, she and Charlie returned to the Citadel and the street mission, where Olive discovered that Milans, now 79 and nearly blind, was living alone in a Detroit hotel. She insisted that he come home with them.

They brought the old man home to Manning Avenue, where they gave him their bedroom and the couple moved into the basement. Milans lived out his remaining days there using a magnifying glass to read and write the 1000s of letters he sent out. By the time of his death in 1946, he had earned the moniker “The Correspondent Evangelist.”

WWII was grinding to a close in 1945 when Charlie got a job offer in Richmond, California, just across the San Francisco Bay from the infamous San Quentin Prison. Prison Warden Clinton Duffy, a Christian dedicated to the reformation and restoration of prisoners, invited Olive and Charlie to bring the new AA meetings to the prison. Charlie and Olive opened the first AA meeting to be held in a prison. Charlie and Olive continued to host the meetings at San Quentin until their move to Los Angeles in 1948.

The story does not end there. Olive and Charlie’s daughter Charla, just 9 when “Grampa” Milans arrived, suffered terribly from dyslexia and was still unable to read. The old man’s tenderhearted compassion won her heart.

In 1949, Charla married her firefighter husband Chuck Pereau. Carrying on the same commitment as their parents to make Christ central in their lives, they taught Sunday school and held prayer meetings in their home. Each year at Christmas, Chuck would put money in the Salvation Army kettle, explaining “There are times when I am on large fires for days without a shower, change of clothes, or food, and The Salvation Army is always there with coffee, hot chocolate, and all the sandwiches you can eat.”

Missions were always at the core of giving for Charla and Chuck, as it had been for Charlie and Olive. A note from a tiny mission in the remote mountains of Oaxaca, Mexico thanked them for a $10 donation and asked if “you consider adopting a yet-to-be-born Zapotec Indian baby?” Shocked, Charla showed Chuck the letter, exclaiming, “Can you believe this? After a mini-sermon from her pastor, she agreed, “Lord, Your will be done.” Then in November 1961, a call came from Texas. “Mrs. Pereau, your son has been born.” Two days later, Charles Curtis arrived. Charla and Chuck would never be the same.

Curtis was about three when he came home with a colored Sunday school paper, with a picture of a little boy, his dog and a ball that carried the caption, “Look What God Has Done for Me!” The question inevitably came: “Chuck, what about all the other little Charles Curtises in Mexico?”

They loaded up Chuck’s pickup truck with food and clothes and headed off to Mexico, only to discover orphanages at the border that were inundated with donations, poorly managed, and filled with dirty children. So they ventured further south. In the middle of the Baja Peninsula, 16 hours’ drive from North Hollywood, they discovered a small group of buildings and a tiny orphanage with 9 children. This would become their mission field.

Fifty years have passed, and orphans led to addict and alcoholic mothers and fathers, which led to prisons, and today the tiny mission started in the Baja has grown to include homes for needy children across Mexico, Christian schools and medical clinics serving the poor, soup kitchens, clothing distribution centers, a Bible institute, prison ministry and of course, a drug and alcohol rehab center.

And where is the life of Henry F. Milans in all of this? At the very core.

His legacy lives on through the lives of those he touched, their children, their grandchildren, and their great-grandchildren. We know, “… unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit” (John 12:24 NRSV).

Right up until his death in 1946, he wrote thousands of letters to heartbroken parents, suffering the pain and scourge of alcoholism, extending the love of Jesus everywhere he went. How should we then live?

Charles Dana Pereau of Federal Way, WA, is the son of Chuck and Charla Davis-Slocum Pereau.